Riding out the apocalypse in a bunker isn’t just for rich people, though they may be the most comfortable when the end times actually come. No one’s exactly comfortable in The End, a somber musical that takes place after the world has ended. Tilda Swinton and Michael Shannon star as the mother and father of George Mackay’s character, a boy born around the time his formerly wealthy father’s dealings in the energy sector might have contributed to the collapse of society.

The mother spends most of her time redecorating the home, recycling through artwork as she hyper-fixates on the most minute details. Father and son, meanwhile, are collaborating on a book about the father’s contributions to the world, though it’s clear that the altruistic person he relays to him is a figment of delusion. These delusions are the heart of The End and though the film struggles to balance its musical elements with its wild story, it’s a fascinating exercise that feels wholly original.

The End Slowly Reveals Its True Intentions

Everything Changes When A Mysterious Stranger Arrives

Very few details are given about how the world actually ended, but it’s hinted that the transition into the bunker was a rough one that led to a lot of people being left behind and a lot more bloodshed when outsiders tried to make their way in. This secrecy is by design. When a stranger arrives (played by the brilliant Moses Ingram), the dynamics of the bunker are constantly under attack, liable to shift at any moment.

Though Mackay’s son is a grown man, his upbringing in the bunker has shielded him from the ugliness of this world. His parents and their friends avoid reality through sheer force of will, but the son is lucky enough to not know any better. When Ingram’s stranger comes along, he must confront the fact that his parents may have been lying to him all along, and they must confront the idea that their underground paradise is as fragile as a house of cards.

Swinton in particular gives a staggering performance as the mother, a masterclass in delusion as she grapples with survivor’s guilt. Initially, it’s unclear whether Swinton or Shannon’s characters feel any regret at all. They seem content to live their lives wrapped in the revisionist stories they tell themselves. Their son is less eager to stay within the confines of this made-up world, especially when the stranger begins forcing all sorts of revelations to the surface.

It starts with a few questions: what happened to the mother’s family? Do they feel bad at all about surviving while so many others faced a brutal demise? Do they think about those who are still out there, struggling in the wasteland of a ruined world? These are enough to send the whole bunker spinning, revealing the delicacy of this shared delusion.

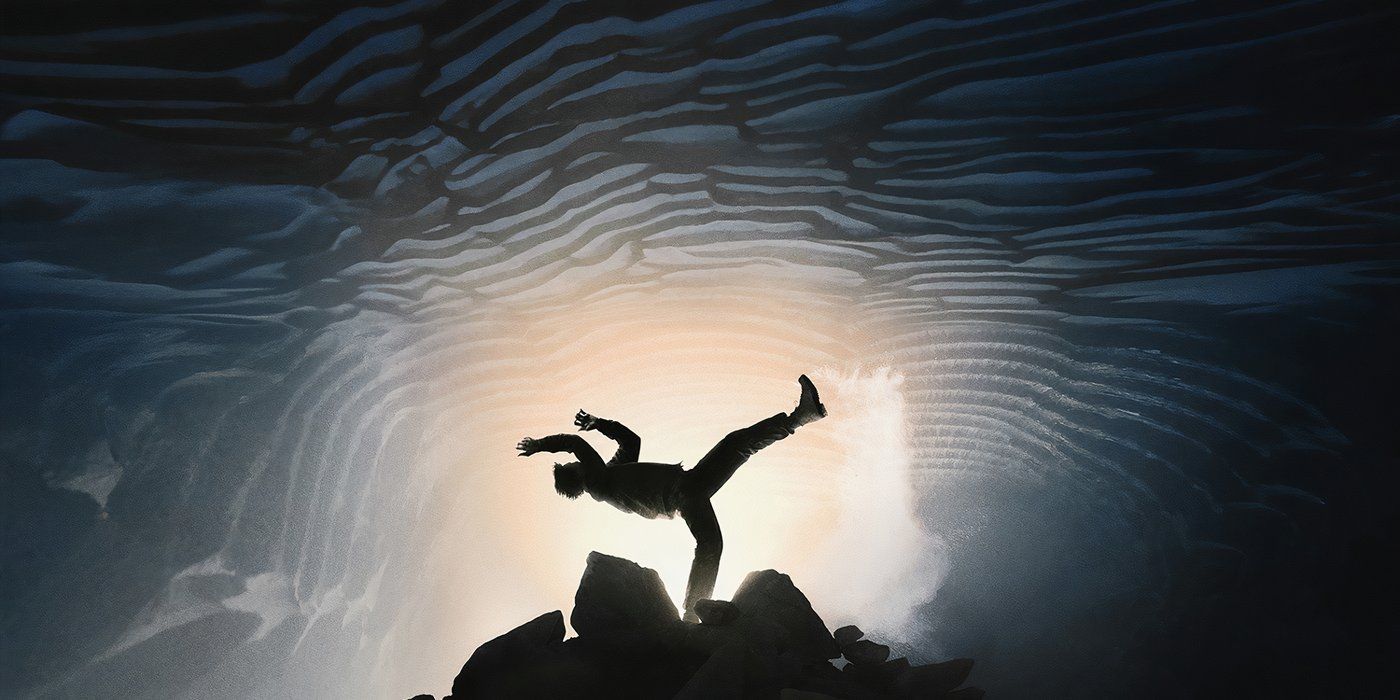

These feelings and more are worked out through song and dance. It’s compelling, but the musical elements eventually wear thin. Most of the numbers are somber affairs, fitting for the film but with little variation to liven up the proceedings. There are bright spots – Mackay gets a dazzling sequence where he dances around the salt mines outside the bunker, Oppenheimer employing wide shots to show how vast the caves are, big enough to fit the family’s fantasies of goodness.

Ingram, too, gives a stunning performance as she navigates this newfound family and grapples with her own guilt, both curious and guarded in her eyes and body. She can’t be sent back outside, but she also can’t stand to live with people so consumed by the lies they tell themselves.

While The End feels as if it goes on a bit too long, repeating the same ideas, it’s still fascinating to watch due to the sheer absurdity of its premise. Oppenheimer directs the hell out of the film, with cinematographer Mikhail Krichman making the bunker and surrounding caves eerie and beautiful. The End is a challenging film and the rewards may be minimal, but that it exists at all is a miracle itself.

The End had its premiere at the 2024 Telluride Film Festival before playing at the Toronto International Film Festival. The film is 148 minutes long and not yet rated.